Зима близко, Странник, полярный лис стучится в дверь.

Bestiary.us

энциклопедия вымышленных существБыстрый переход

- Средневековые бестиарии Бестиарии практически составляли особый жанр в средневековой литературе, совмещавший в себе черты естественнонаучного сочинения, теологического трактата и художественных произведений, и рассказывающий нам о представлениях средневековой Европы о животных и чудовищных племенах.

- Портал им.Киплинга Собрание сказок, поэтически объясняющих происхождение той или иной особенности животных, например "откуда у верблюда горб", "почему у слона длинный хобот", или "с чего б это вдруг кошки и собаки не ладят".

- Бестиарий «Волчонка» Материалы портала посвящены мифологии сериала "Волчонок" (Teen Wolf), различным легендам и поверьям о вервольфах и других существах, встречаемых в сериале.

Тламхиген-и-дурр

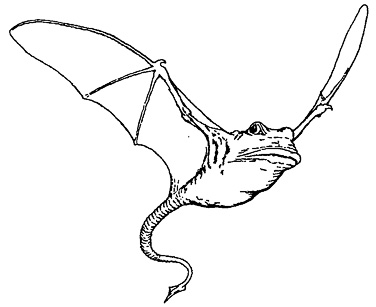

Тламхиген-и-дурр — чудовище из валлийского фольклора, огромная жаба с крыльями летучей мыши и змеиным хвостом

Llamhigyn Y Dwr — a monster from Welsh folklore, a huge toad with bat wings and a snake tail

Тламхиген-и-дурр — чудовище из валлийского фольклора, огромная жаба с крыльями летучей мыши и змеиным хвостом

Llamhigyn Y Dwr — potwór z folkloru walijskiego, jest to ogromna ropucha ze skrzydłami nietoperza i wężowym ogonem

Тламхиген-и-дурр — чудовище из валлийского фольклора, огромная жаба с крыльями летучей мыши и змеиным хвостом

Тламхиген-и-дуррЧудовище из валлийского фольклора, огромная жаба с крыльями летучей мыши и змеиным хвостом по-русскиLlamhigyn Y DwrA monster from Welsh folklore, a huge toad with bat wings and a snake tail in englishLlamhigyn Y DwrPotwór z folkloru walijskiego, jest to ogromna ropucha ze skrzydłami nietoperza i wężowym ogonem w polskim

Llamhigyn Y Dwr —

Skakun wodny —

Water-Leaper —

Водяной попрыгун —

Ламхигин-и-дур —

Лламигин-и-дор —

Лламхигин-и-дур —

Лэмхайджин Вай Дувр —

Прыгун в воду —

"Водяной попрыгун — это злой дух из сказок валлийских рыбаков, нечто вроде водяного демона, который рвал сети, пожирал упавших в реки овец и часто издавал ужасный крик, который так пугал рыбаков, что водяной попрыгун мог стащить свою жертву в воду, где несчастный разделял участь овцы. Уильям Джонс из Лланголлена говорил, что это чудовище похоже на огромную жабу с крыльями и хвостом вместо лап" (307: с.376):

'Besides those, who used to come to my grandfather's house and to his workshop to relate stories, the blacksmith's shop used to be, especially on a rainy day, a capital place for a story, and many a time did I lurk there instead of going to school, in order to hear old William Dafydd, the sawyer, who, peace be to his ashes! drank many a hornful from the Big Quart without ever breaking down, and old Ifan Owen, the fisherman, tearing away for the best at their yarns, sometimes a tissue of lies and sometimes truth. The former was funny, and a great wag, up to all kinds of tricks. He made everybody laugh, whereas the latter would preserve the gravity of a saint, however lying might be the tale which he related. Ifan Owen's best stories were about the Water Spirit, or, as he called it, Llamhigyn y Dwr, "the Water Leaper". He had not himself seen the Llamhigyn, but his father had seen it "hundreds of times." Many an evening it had prevented him from catching a single fish in Llyn Gwynan, and, when the fisherman got on this theme, his eloquence was apt to become highly polysyllabic in its adjectives. Once in particular, when he had been angling for hours towards the close of the day, without catching anything, he found that something took the fly clean off the hook each time he cast it. After moving from one spot to another on the lake, he fished opposite the Benlan Wen, when something gave his line a frightful pull, "and, by the gallows, I gave another pull," the fisherman used to say, "with all the force of my arm: out it came, and up it went off the hook, whilst I turned round to see, as it dashed so against the cliff of Benlan that it blazed like a lightning." He used to add, "If that was not the Llamhigyn, it must have been the very devil himself." That cliff must be two hundred yards at least from the shore. As to his father, he had seen the Water Spirit many times, and he had also been fishing in the Llyn Glâs or Ffynnon Lâs, once upon a time, when he hooked a wonderful and fearful monster: it was not like a fish, but rather resembled a toad, except that it had a tail and wings instead of legs. He pulled it easily enough towards the shore, but, as its head was coming out of the water, it gave a terrible shriek that was enough to split the fisherman's bones to the marrow, and, had there not been a friend standing by, he would have fallen headlong into the lake, and been possibly dragged like a sheep into the depth; for there is a tradition that if a sheep got into the Llyn Glâs, it could not be got out again, as something would at once drag it to the bottom. This used to be the belief of the shepherds of Cwm Dyli, within my memory, and they acted on it in never letting their dogs go after the sheep in the neighbourhood of this lake. These two funny fellows, William Dafydd and Ifan Owen, died long ago, without leaving any of their descendants blessed with as much as the faintest gossamer thread of the story-teller's mantle. The former, if he had been still living, would now be no less than 129 years of age, and the latter about 120' (635: Vol.I, p.78-80).

"Среди тех, кто обычно приходил в дом моего деда и в его мастерскую, попадались любители потравить байки, а кузница, особенно в дождливый день, была отличным местом для историй, и сам я, вместо того, чтобы ходить в школу, часто прятался там, слушая старого Уильяма Дэффида, пильщика, который — мир его праху! — выпил столько рогов в "Большой Кварте", ни разу не сломавшись, и старого рыбака Ифана Оуэна, стараясь изо всех сил запомнить их байки, иной раз сплетенные из одной лжи, а иногда и из правды. Первый был забавным и большим остряком, доводя всех до смеха своими проделками. Второй же сохранял серьезность святого, какой бы лживой ни была рассказываемая им история. Лучшие рассказы Ифана Оуэна были о водяном духе, или, как он его называл, Тламхиген-и-дурре, "водяном прыгуне". Сам он не видел Тламхигена, но его отец встречал его "сотни раз". Часто по вечерам это мешало ему поймать хоть какую рыбку в Ллин-Гвинанте, и когда рыбак затрагивал эту тему, его красноречие пестрило многосложными эпитетами. Так, однажды он несколько часов ловил вечером рыбу и, ничего не поймав, обнаружил, что что-то срывает мушку с крючка каждый раз, как он ее забрасывал. Перебравшись с одного места озера на другое, он рыбачил напротив Бенлан-Вен, когда что-то страшно рвануло леску, "И, клянусь виселицей, — вещал рыбак, — Я дернул еще раз изо всех сил: оно выплыло, и показавшись, сорвалось с крючка, я лишь успел обернуться, глядя, как сверкнула, будто молния, его шкура от удара о скалу Бенлан". Обычно он добавлял: "Если это был не Тламхиген, то, должно быть — сам дьявол". Этот утес, вероятно, находится по меньшей мере в двухстах ярдах* от берега. Что касается его отца, то он, якобы, много раз видел водяного, а однажды рыбача в Ллин-Гласе или Ффиннон-Ласе, поймал на крючок чудное и страшное чудище: оно не было похоже на рыбу, а скорее напоминало жабу, за исключением того, что у него вместо ног был хвост и крылья. Рыбак довольно легко подтянул его к берегу, но, когда голова существа показалась из воды, оно издало ужасный вопль, способный раздробить ноги до мозга костей, и, если бы рядом не было товарища, рыбак упал бы головой в озеро, и возможно, тогда его утащили бы, как овцу, на дно; недаром ведь говорят, что если овца попадала в Ллин-Глас, ее уже было не вытащить, так как что-то сразу же утаскивало ее на дно. Насколько я помню, раньше в это верили пастухи из Кум-Дугли (Cwm Dyli), и они, в соответствии с этим, никогда не позволяли своим собакам гонять овец по соседству с этим озером. Два этих забавных парня, Уильям Дэффидд и Ифан Оуэн, умерли давным-давно, не оставив ни одному из своих потомков даже тончайшей нити мантии рассказчика. Первому, будь он еще жив, сейчас бы было не менее 129 лет, а второму — около 120" (635: Vol.I, p.78-80).

По одним источникам прыгун совсем не имеет лап, по другим — крылья заменяют ему лишь передние лапы. "Если хвост этого странного существа является остатком хвоста головастика, не редуцировавшегося при метаморфозе, то Лламхигин-и-дур может считаться двойной химерой — жаба + летучая мышь." (311: с.122-123)

Также статья о нем есть в бестиарии Сапковского:

Llamhigyn Y Dwr (skakun wodny) — jest to monstrum, na sam widok którego co słabsi duchem mdleją ze zgrozy. Bytuje w rzekach Walii, a przypomina ropuchę — ale wielkości byka. Ma ogromną paszczękę i wyłupiaste ślepia, a odgłosy, jakie wydaje, przypominają kumkanie i skrzeczenie. Potrafi jednak, gdy chce, wydać przeraźliwy i mrożący krew w żyłach krzyk. Jest beznogi, ale ma parę błoniastych skrzydeł i długi, wężowy ogon. Dzięki skrzydłom i ogonowi potrafi wyskoczyć spod wody z szybkością błyskawicy, złapać co trzeba i znowu zniknąć w rzecznej toni.

Słyszano o przypadkach, gdy skakun pożerał ludzi, ale głównym jego pożywieniem są owce i inne zwierzaki, które pasą się w pobliżu rzeki lub mają pecha do niej wpaść. Wiadomo ponad wszelką wątpliwość, że Llamhigyn Y Dwr nie znosi wędkarzy — nigdy nie przepuści okazji, by poplątać i pozaczepiać im wędki, brodzącym zaś w woderach podkłada przysłowiowe kłody pod nogi, by się wywalili. Tych, którzy się wywalą, Llamhigyn oplata ogonem i topi, po czym wlecze do swego podwodnego leża i tam trzyma, aż się porządnie zaśmierdzą i skruszeją, wtedy ich pożera (747: s.196).

"Водный прыгун, монстр, при одном только виде которого слабые духом падают в обморок. Проживает он в реках Валлии и похож на лягушку, раздувшуюся до размеров быка. У него огромная пасть и выпученные глазищи, а издаваемые им звуки напоминают кваканье и скрип. Однако при желании он может издать истошный крик, от которого кровь стынет в жилах. Он безног, но имеет пару перепончатых крыльев и длинный змеиный хвост. Благодаря крыльям и хвосту ухитряется молниеносно выпрыгнуть из-под воды, схватить добычу и вновь скрыться в речной глубине.

Поговаривали о случаях, когда прыгун пожирал людей, но в основном он питается овцами и другими травоядными, которые пасутся вблизи реки или же имеют несчастье в нес свалиться. Точно известно, что лламигин-и-дор терпеть не может рыбаков с удилищами, никогда не упустит случая перепутать им лески и зацепить за что-нибудь крючки, а рыбакам, которые носят высокие болотные сапоги, "ставит палки в колеса", то есть подбрасывает что-нибудь под ноги, лишь бы они свалились в воду. Свалившихся лламигин-и-дор оплетает хвостом, топит, затем уволакивает в свое подводное логово и там держит до тех пор, пока они как следует не протухнут и не разложатся, после чего пожирает" (49: с.351-352).

Несколько видоизмененным Llamhigyn Y Dwr появляется в играх Final Fantasy XI и 2Moons.

Llamhigyn Y Dwr [thlamheegin er doorr], or the Water-Leaper was the villain of Welsh fishermen's tales, a kind of water-demon which broke the fishermen's lines, devoured sheep which fell into the rivers, and was in the habit of giving a fearful shriek which startled and unnerved the fisherman so that he could be dragged down into the water to share the fate of the sheep. Rhys, from a second-hand account of it given him by William Jones of Llangollen, learned that this monster was like a gigantic toad with wings and a tail instead of legs (1290: p.270):

'Besides those,' Mr. Jones goes on to say, 'who used to come to my grandfather's house and to his workshop to relate stories, the blacksmith's shop used to be, especially on a rainy day, a capital place for a story, and many a time did I lurk there instead of going to school, in order to hear old William Dafydd, the sawyer, who, peace be to his ashes! drank many a hornful from the Big Quart without ever breaking down, and old Ifan Owen, the fisherman, tearing away for the best at their yarns, sometimes a tissue of lies and sometimes truth. The former was funny, and a great wag, up to all kinds of tricks. He made everybody laugh, whereas the latter would preserve the gravity of a saint, however lying might be the tale which he related. Ifan Owen's best stories were about the Water Spirit, or, as he called it, Llamhigyn y Dwr, "the Water Leaper". He had not himself seen the Llamhigyn, but his father had seen it "hundreds of times." Many an evening it had prevented him from catching a single fish in Llyn Gwynan, and, when the fisherman got on this theme, his eloquence was apt to become highly polysyllabic in its adjectives. Once in particular, when he had been angling for hours towards the close of the day, without catching anything, he found that something took the fly clean off the hook each time he cast it. After moving from one spot to another on the lake, he fished opposite the Benlan Wen, when something gave his line a frightful pull, "and, by the gallows, I gave another pull," the fisherman used to say, "with all the force of my arm: out it came, and up it went off the hook, whilst I turned round to see, as it dashed so against the cliff of Benlan that it blazed like a lightning." He used to add, "If that was not the Llamhigyn, it must have been the very devil himself." That cliff must be two hundred yards at least from the shore. As to his father, he had seen the Water Spirit many times, and he had also been fishing in the Llyn Glâs or Ffynnon Lâs, once upon a time, when he hooked a wonderful and fearful monster: it was not like a fish, but rather resembled a toad, except that it had a tail and wings instead of legs. He pulled it easily enough towards the shore, but, as its head was coming out of the water, it gave a terrible shriek that was enough to split the fisherman's bones to the marrow, and, had there not been a friend standing by, he would have fallen headlong into the lake, and been possibly dragged like a sheep into the depth; for there is a tradition that if a sheep got into the Llyn Glâs, it could not be got out again, as something would at once drag it to the bottom. This used to be the belief of the shepherds of Cwm Dyli, within my memory, and they acted on it in never letting their dogs go after the sheep in the neighbourhood of this lake. These two funny fellows, William Dafydd and Ifan Owen, died long ago, without leaving any of their descendants blessed with as much as the faintest gossamer thread of the story-teller's mantle. The former, if he had been still living, would now be no less than 129 years of age, and the latter about 120' (635: Vol.I, p.78-80).

Llamhigyn Y Dwr (skakun wodny) — jest to monstrum, na sam widok którego co słabsi duchem mdleją ze zgrozy. Bytuje w rzekach Walii, a przypomina ropuchę — ale wielkości byka. Ma ogromną paszczękę i wyłupiaste ślepia, a odgłosy, jakie wydaje, przypominają kumkanie i skrzeczenie. Potrafi jednak, gdy chce, wydać przeraźliwy i mrożący krew w żyłach krzyk. Jest beznogi, ale ma parę błoniastych skrzydeł i długi, wężowy ogon. Dzięki skrzydłom i ogonowi potrafi wyskoczyć spod wody z szybkością błyskawicy, złapać co trzeba i znowu zniknąć w rzecznej toni.

Słyszano o przypadkach, gdy skakun pożerał ludzi, ale głównym jego pożywieniem są owce i inne zwierzaki, które pasą się w pobliżu rzeki lub mają pecha do niej wpaść. Wiadomo ponad wszelką wątpliwość, że Llamhigyn Y Dwr nie znosi wędkarzy — nigdy nie przepuści okazji, by poplątać i pozaczepiać im wędki, brodzącym zaś w woderach podkłada przysłowiowe kłody pod nogi, by się wywalili. Tych, którzy się wywalą, Llamhigyn oplata ogonem i topi, po czym wlecze do swego podwodnego leża i tam trzyma, aż się porządnie zaśmierdzą i skruszeją, wtedy ich pożera (747: s.196).

Онлайн источникиАнлайн крыніцыŹródła internetoweОнлайн джерелаOnline sources

Статус статьиСтатус артыкулаStatus artykułuСтатус статтіArticle status:

Зверушка (вроде готовая статья, но при этом велика вероятность расширения)

Подготовка статьиПадрыхтоўка артыкулаPrzygotowanie artykułuПідготовка статтіArticle by:

Адрес статьи в интернетеАдрас артыкулу ў інтэрнэцеAdres artykułu w internecieАдрес статті в інтернетіURL of article: //bestiary.us/tlamhigen-i-durr

Культурно-географическая классификация существ:

Культурна-геаграфічная класіфікацыя істот:

Kulturalno-geograficzna klasyfikacja istot:

Культурно-географічна класифікація істот:

Cultural and geographical classification of creatures:

Ареал обитания:

Арэал рассялення:

Areał zamieszkiwania:

Ареал проживання:

Habitat area:

Псевдо-биологическая классификация существ:

Псеўда-біялагічная класіфікацыя істот:

Pseudo-biologiczna klasyfikacja istot:

Псевдо-біологічна класифікація істот:

Pseudo-biological classification of creatures:

Физиологическая классификация:

Фізіялагічная класіфікацыя:

Fizjologiczna klasyfikacja:

Фізіологічна класифікація:

Physiological classification:

Вымышленные / литературные миры:

Выдуманыя / літаратурныя сусветы:

Wymyślone / literackie światy:

Вигадані / літературні світи:

Fictional worlds:

Форумы:

Форумы:

Fora:

Форуми:

Forums:

Еще? Еще!

Левиафан — в преданиях Древнего Востока и в Библии гигантское морское чудовище

Бука (Bwca) — валлийская разновидность брауни, домашний дух-помощник

Гвиллионы — злые горные эльфы Уэльса, безобразные существа женского пола, которые по ночам подстерегают путников на горных дорогах и сбивают их с пути

Терлоитх тейг — крошечные добрые эльфы валлийского фольклора, чье название буквально переводится как "дивная семейка"

Пьючен — в мифологии коренного населения Чили, Перу и Аргентины вампир-оборотень в облике змеи с крыльями летучей мыши

Бендит-и-Мамай — южно-валлийские фейри, которые совершают конные выезды, навещают людские дома и похищают детей

Куэро — в мифологии южноамериканского народа мапуче, водяной вампир в виде распластанной бычьей кожи с рачьими глазами и когтями по периметру

Портуны — в английском и валлийском фольклоре питающиеся лягушками фейри, помогающие по хозяйству, но и не упускающие возможности подшутить над людьми

Уббе — у казахов демонический персонаж, прекрасная девушка, в которую превращается дракон айдахар, прожив 100 или 1000 лет

Горгульи — уродливые существа, химеры, произошедшие от названия выходов водосточных жёлобов в готических соборах

Подменыш — ребенок нечистой силы (эльфов, русалок, леших, чертей и других), подброшенный вместо похищенного новорожденного

Мичибичи — в мифах алгонкинских племен Северной Америки водное божество, владыка всех рыб, обычно изображаемый как водная пантера с лицом человека

Ламия — в античной мифологии полудева-полузмея, демоница, сосущая кровь своих жертв

Фера — общее название перевертышей мира Тьмы (игра «Werewolf: the Apocalypse»)

Comments

http://dreamea.narod.ru/bestia/mith/best2/bestiariylx2.html#LLAMHIGYN

http://aiofa.deviantart.com/art/Llamhigyn-Y-Dwr-110317879

http://felarya.forumotion.com/new-ideas-f2/llamhigyn-y-dwr-t572.htm

http://www.batcow.co.uk/strangelands/dragons.htm

Наиболее близким к оригинальному звучанию на валлийском будет "лламhигын а дур", с английской "не хриплой" h, ударением на "и" и долгим "у". Хотя в начале там все-таки не "лл", а глухой "л", который очень похож на тот звук, который можно услышать в начале того слова, которым маленькие дети называют хлеб: "щлеб" или как-то так :)

Ого, круто, спасибо. Надо будет как-то в статью добавить.

Отправить комментарий